Douglas McIntyre looks at the best and worst run states in America according to this year’s 24/7 Wall Street study.

How well run is your state? Assessing a state's management quality is no simple task. The current economic climate and standard of living in any given state are not only the results of recent policy choices and developments, but may also be dependent on forces outside a state's control and, often, decisions made decades ago.

For each of the past six years, 24/7 Wall St. has attempted to answer this question by surveying various characteristics of each state. To determine how well states are managed, we examine key financial ratios, as well as social and economic outcomes. This year, North Dakota is the best-run state in the country for the fourth consecutive year, while New Mexico replaced Illinois as the worst-run state.

See where all the states rank:

BEST-RUN STATES:

1. North Dakota

> Debt per capita: $2,481 (18th lowest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AAA/Aa1

> Unemployment rate: 2.8% (the lowest)

> Median household income: $59,029 (15th highest)

> Poverty rate: 11.5% (8th lowest)

North Dakota is the nation's best-run state for the fourth consecutive year. The state's position at the top is largely due to its abundant natural resources, which helped fuel the state's oil boom over the past several years. The mining industry contributed 2.5 percentage points to North Dakota's 6.3% economic growth in 2014 — the fastest growth rate of any state. The state, with its nation-leading 2.8% unemployment rate, has attracted large numbers of workers seeking high-paying jobs that require relatively little experience or education. Net migration over the five years through 2014 accounts for 6.6% of North Dakota's current population, the largest share of any state. The remarkable population growth is a testament to the state's economic strength over the past several years.

Despite the rapid growth, North Dakota may be overly reliant on its resources. With oil prices plummeting in the past year, the total number of mining jobs dropped by 17.2% over the 12 months through October. Without a strong mining industry, could North Dakota keep its high ranking? That will be the true test of a well-run state.

2. Wyoming

> Debt per capita: $1,747 (7th lowest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AAA/ N/A

> Unemployment rate: 4.0% (11th lowest)

> Median household income: $57,055 (18th highest)

> Poverty rate: 11.2% (5th lowest)

For years, Wyoming has placed well in the annual ranking of best-run states. One factor may be the state's relatively manageable size. Home to just over half a million people, Wyoming is the least populated state in the country. Wyoming's state budget proceedings are particularly well run. According to an annual report on corruption from The Center for Public Integrity, Wyoming earns the third highest marks for its budgetary process. Wyoming's rainy day fund is equal to 54.1% of annual general fund expenditures, the second largest state rainy day fund in the nation. Only in Alaska is the share larger, and the average state's reserve is equal to only 5.4% of spending. Furthermore, Wyoming's debt as a percent of annual revenue is only 13.5%, the smallest share in the country, contributing to its second-place ranking. By contrast, the average state's debt as a percent of annual revenue is 51.3%.

Wyoming residents are also relatively well off financially. Only 11.2% of Wyoming residents live in poverty, the fifth lowest poverty rate of any state.

3. Iowa

> Debt per capita: $2,140 (12th lowest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AAA/Aaa

> Unemployment rate: 3.5% (6th lowest)

> Median household income: $53,712 (21st highest)

> Poverty rate: 12.2% (14th lowest)

With the highest possible credit rating from both Moody's and S&P, as well as a stable outlook, Iowa is one of the best-run states in the country. Competent management has likely led to many of the positive outcomes in the state. More than 92% of adults in theHawkeye State have graduated from high school, a higher share than in all but a handful of other states. Also, Iowa's unemployment rate is one of the lowest in the country. As of October, only five states had a lower unemployment rate than Iowa.

Home values in Iowa are increasing at a much faster rate than they are across the nation. The value of a typical home in Iowa rose by nearly 8% from 2010 through 2014, much faster than the nationwide increase of less than 1% over that time. The relatively rapid rise in home values may indicate rising incomes, increased demand, or a combination of the two.

4. Nebraska

> Debt per capita: $981 (2nd lowest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AAA/ N/A

> Unemployment rate: 2.9% (2nd lowest)

> Median household income: $52,686 (24th highest)

> Poverty rate: 12.4% (16th lowest)

In much of the Midwest, agriculture-driven states have benefitted from the stability of the industry, and Nebraska is no different. Though the agriculture industry was impacted by the recession, the economic damage it sustained was minor in comparison to many other U.S. industries. Like its neighbors, Nebraska has had low unemployment for years. The state's current unemployment rate of 2.9% is the second lowest in the country behind only North Dakota.

Nebraska collects $2,508 per capita each year in taxes, less than the national average of $2,657. Still, the state has a relatively balanced budget. The state government could pay 80% of its pension fund obligations. Nebraska's government debt in 2013 of just $981 per state resident was the second smallest in the country.

5. Minnesota

> Debt per capita: $2,487 (19th lowest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AA+/Aa1

> Unemployment rate: 3.7% (8th lowest)

> Median household income: $61,481 (10th highest)

> Poverty rate: 11.5% (8th lowest)

A typical household in Minnesota earns $61,481 annually, significantly more than the $53,657 the typical American household earns. With a solid tax base, the state is able to collect $3,854 per capita annually, a larger tax revenue than all but a handful of other states. Perhaps the state is better able to manage its finances as a result. The state's debt is equal to less than 30% of its annual revenue. By contrast, the average state's debt as a percent of annual revenue is 51.3%.

Few states allocate a larger share of their annual budget to education than Minnesota. On average, states spend 35.6% of annual budgets on education, while Minnesota spends 42.9%. Higher spending may partially explain the higher educational attainment among state residents, which in turn contributed to Minnesota's high ranking. After Alaska, Minnesota is home to the highest share of adults with a high school diploma. Additionally, 34.3% of adults in the state have a bachelor's degree, higher than the national rate of 30.1%.

WORST-RUN STATES

50. New Mexico

> Debt per capita: $3,468 (22nd highest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AA+/Aaa

> Unemployment rate: 6.8% (2nd highest)

> Median household income: $44,803 (8th lowest)

> Poverty rate: 21.3% (2nd highest)

New Mexico is the worst-run state in the country with some of the worst social and economic outcomes. Only a handful of states struggle with similar levels of extreme poverty as New Mexico. More than one in every 10 households in the state earns less than $10,000 each year, the second highest proportion after Mississippi. The state also struggles with one of the nation's highest violent crime rates. Close to 600 violent crimes are reported each year per 100,000 state residents, one of the highest rates nationwide.

Like a number of other states towards the bottom of this list, more people left New Mexico than arrived from April of 2010 through the middle of last year. Only Illinois reported a larger net population decline over that period.

49. Illinois

> Debt per capita: $4,942 (11th highest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): A-/Baa1

> Unemployment rate: 5.4% (16th highest)

> Median household income: $57,444 (17th highest)

> Poverty rate: 14.4% (25th lowest)

Illinois collects more than $3,000 per capita in state and local taxes each year, one of the highest per capita tax revenues. Yet, the state's fiscal management system does not appear to be operating optimally, which is the main reason it ranks as the second worst-run state. For example, Illinois has one of the smallest rainy day funds compared to other states, at 1% of its general annual budget — an indication the state may not be able to satisfy its short-term obligations. Illinois' debt is equal to more than three-fourths of its annual revenue, also one of the highest shares in the nation. Similarly, the state's pension fund is not financially healthy. The state only has assets on hand to meet 39% of its pension obligations, the lowest ratio of any state. Perhaps as a result of the state's finances, Illinois has the worst credit rating and outlook from S&P and Moody's of any state.

The housing market in Illinois is also struggling. One in every 73 housing units is in some state of the foreclosure process, nearly the highest foreclosure rate in the country. As is often the case in states with particularly high foreclosure rates, home prices in Illinois have dropped by more than 10% from 2010 through last year. This decline was the worst in the country during that time.

48. Mississippi

> Debt per capita: $2,376 (15th lowest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AA/Aa2

> Unemployment rate: 5.9% (9th highest)

> Median household income: $39,680 (the lowest)

> Poverty rate: 21.5% (the highest)

It may not be surprising to find what may be the worst economy in the country ranked as the third worst-run state. The typical household in Mississippi earns just $39,680 a year, the lowest such amount in the country. Similarly, 21.5% of Mississippi residents live in poverty, the highest poverty rate nationwide. The job climate is also dismal. Mississippi's unemployment rate of 5.9% is the ninth highest in the nation. From 2010 through 2014, the state's workforce shrank by 5.4%, while the country's workforce grew by 6.7%. In the same time period, as a result of people moving in and out of the state, Mississippi's total population shrank by 0.6%, the fifth largest net migration decline of any state.

47. Rhode Island

> Debt per capita: $9,068 (2nd highest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AA/Aa2

> Unemployment rate: 5.3% (17th highest)

> Median household income: $54,891 (19th highest)

> Poverty rate: 14.3% (24th lowest)

After Massachusetts, its neighbor to the north, Rhode Island's debt per capita is the second highest in the nation, contributing to its rank as the fourth worst-run state. While the average state debt per capita across all states is $3,567, Rhode Island's debt is equal to $9,068 per state resident. With a dwindling tax base, conditions may get worse in the Ocean State before they get better. Rhode Island lost roughly 0.3% of its total population to people relocating from 2010 through 2014, making it one of 12 states with more people moving out than moving in. The population decline likely contributed to the even sharper drop in property values. Home prices in Rhode Island decreased by 7.3% over roughly the same time period, the fourth steepest drop in the country.

Budget allocation in Rhode Island may not be efficient. While the state spends much more on government than is typical, at 5.4% of its annual budget, the government sector actually detracted 0.2 percentage points from the state's 2014 GDP growth, a larger drag than in all but six other states.

46. Alabama

> Debt per capita: $1,867 (8th lowest)

> Credit rating (S&P/Moody's): AA/Aa1

> Unemployment rate: 5.9% (9th highest)

> Median household income: $42,830 (4th lowest)

> Poverty rate: 19.3% (4th highest)

Alabama's poor social and economic outcomes led to its rank as the fifth worst-run state. Alabama's per capita tax revenue is only $1,911 — a smaller amount than in all but a handful of other states. The state's weak tax revenue is due in part to low incomes among its residents. The typical Alabama household makes just $42,830 annually, significantly less than the national average of $53,657. Furthermore, nearly one-fifth of state residents live below the poverty line, a higher poverty rate than in all but three other states. Also, Alabama's 5.9% unemployment rate is among the highest in the country. Benefits for the state's unemployed workers are among the lowest in the nation. Across the country, the average unemployment insurance beneficiary receives about $321 a week. In Alabama, the average weekly unemployment insurance payout is only $214.

Economic growth in the state is sluggish. While the national economy expanded by 2.2% in 2014, Alabama's economy grew by only 0.7% in the same time period.

More on methodology

There is no comprehensive measure of a state government administration and how well or poorly it runs the state. Selecting appropriate criteria to compare the 50 states is difficult because there is so much variation among them. Some states are rich in natural resources, for example, while others rely on high-skilled sectors, such as technology and business services. Some depend disproportionately on one industry, while economies in other states are more balanced. Further, some states are more rural, while others are highly urbanized and densely populated.

As a result, policy decisions that may work in one state might not work in another. For example, while taking on large amounts of debt to fund a state's spending is often fiscally irresponsible, wealthier states arguably benefit from higher debt levels — they can use the extra funds to pay for public welfare services and are able to pay it back without much effort.

Most of the conditions used to determine how well or poorly run a state is do not tend to fluctuate a great deal from year to year. Measures such as income, poverty, and violent crime rates do not usually change meaningfully from year to year. Still, the rank of some states changed significantly this year. Maine, West Virginia, and Alaska each regressed by at least 10 spots. Alaska, this year's 18th-best run state, was seventh-best last year. Meanwhile, four states improved by nearly 10 spots. Colorado improved from 17th-best to eighth-best.

This year, a number of the best-run states have again benefited from an abundance of natural resources, although this can often manifest as an overreliance. North Dakota, Wyoming, and Texas are among the top 10 best-run states, and in all three, the mining industry — which includes fossil fuel extraction — is a major contributor to state GDP. Due in large part to the mining sector, North Dakota, Texas and Wyoming led the nation in real GDP growth in 2014. Alaska has utilized its oil wealth to build massive state reserves and to pay its residents an annual dividend. However, the state's position fell this year largely due to falling oil prices. Similarly, while North Dakota is the leader again this year, the mining industry has been subject to wild fluctuations.

While some states' economic fortunes are closely tied to the rise and fall of individual industries, which are often outside their control, each state must make the best of its own situation. Governments, as stewards of their own economies, need to prepare for the worst, including the collapse of a vital industry. Good governance is about balancing tax collection and state expenditure in a way that provides essential services to residents without sacrificing a state's long-term fiscal health. Many of the best-run states in the country set money aside each year for emergencies. For example, Alaska's rainy day fund — reserves set aside to be allocated in the event of unforeseen budget shortfalls — are equal to 146.4% of its revenue, the highest such percentage of any state.

While each state is different, states at both ends of the list share certain characteristics. For example, people living in the worst-run states tend to have lower standards of living. Violent crime and poverty rates are typically higher in these states, and the share of the population with at least a high school diploma tends to be lower than the national rate.

The worst-run states also tend to have weak fiscal management, reflected by low pension funding, sparsely padded coffers, and poor credit ratings from Moody's Investors Service and Standard & Poor's (S&P). Illinois, the second worst-run state in America, received lower ratings than any other state from both agencies. By contrast, the majority of the 10 best-run states have perfect ratings from both agencies.

Unemployment rates are also relatively low in the nation's best-run states. North Dakota, the top-ranked state, has an unemployment rate of 2.8%, the lowest of all states. Six of the 10 best-run states have among the 10 lowest unemployment rates. Meanwhile, unemployment is much more prevalent in the worst-run states. Louisiana and New Mexico, both among the lowest-ranked states, have the nation's fifth- and second-highest unemployment rates, at 6.2% and 6.8%, respectively.

To determine how well each state is run, 24/7 Wall St. constructed an index of numerous measures from a variety of sources. From the U.S. Census Bureau, we looked at net migration to a state from April 2010 to July 2014 as a percentage of the population in 2014. We reviewed each state's finances for the 2013 fiscal year, including revenue, per capita tax collection, expenditure and debt levels, all from the Census. In addition, we considered pension funding ratios for each state fromWashington D.C.-based think tank The Pew Research Center, as well as each state's rainy day fund balance as a percentage of total general fund expenditures estimated for fiscal 2015 from The National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO). For Georgia and Oklahoma, for which fiscal 2015 estimates were not available, we used the balance for fiscal 2014. NASBO defines rainy day funds as "budget stabilization funds set aside to respond to unforeseen circumstances." Government general obligation ratings were provided by Standard & Poor's and Moody's Investors Service.

From the U.S. Census Bureau's 2014 American Community Survey (ACS), we also considered a range of socioeconomic factors to assess social outcomes and residents' well-being. We looked at poverty, educational attainment, the percentage of adults without health insurance, and median household income. Violent crime rates came from the Federal Bureau of Investigation's (FBI) 2014 Uniform Crime Report. Annual foreclosure rates, measured as the number of housing units at some stage in the foreclosure process, were provided by housing market data tracker RealtyTrac and are for 2014.

To evaluate each state's job market, we reviewed annual 2014 unemployment rates as well as jobless rates as of October from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Characteristics of each state's unemployment insurance (UI) benefits system, including average weekly benefit amounts in dollars and as a percentage of the average weekly wage (the replacement rate), the percentage of UI claimants exhausting their benefits before finding a job (the exhaustion rate), the average duration in weeks of insurance benefits, and the percentage of unemployed individuals receiving UI benefits (the recipiency rate) are from the Department of Labor's Employment and Training Administration (DOLETA) and are as of 2014.

Lastly, to assess the strength of each state's economy, we reviewed real GDP growth rates in 2014 from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). Also from the BEA, we considered industry contributions to a state's economic growth in 2014, as well as 2013 regional price parity, a proxy for an area's cost of living.

Matt Krantz

Matt Krantz

The creation of Léon Theremin’s bug can be attributed to the success of his instrument. Theremin, the man, was a scientist by training. Theremin,

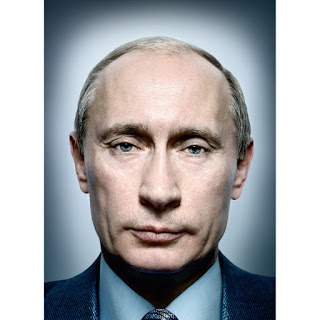

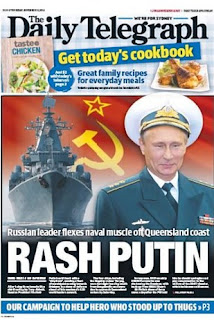

The creation of Léon Theremin’s bug can be attributed to the success of his instrument. Theremin, the man, was a scientist by training. Theremin, The date was August 4, 1945. The european war was over, and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima was only two days away. A group of 10 to 15 year old boys from the Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union arrived at the US embassy carrying a hand carved great seal of the United States of America. They presented the seal to W. Averell Harriman, the US ambassador to the Soviet Union. The seal was given as a gesture of friendship between the US and Soviet Union. Harriman hung the plaque in the study of his residence, Spaso House. Unbeknownst to Harriman, the seal contained Theremin’s sophisticated listening device. The device, later known as “The Thing”, would not be discovered until 1952 — roughly seven years later.

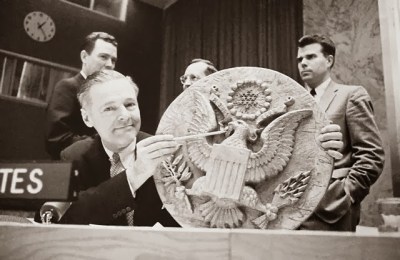

The date was August 4, 1945. The european war was over, and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima was only two days away. A group of 10 to 15 year old boys from the Young Pioneer Organization of the Soviet Union arrived at the US embassy carrying a hand carved great seal of the United States of America. They presented the seal to W. Averell Harriman, the US ambassador to the Soviet Union. The seal was given as a gesture of friendship between the US and Soviet Union. Harriman hung the plaque in the study of his residence, Spaso House. Unbeknownst to Harriman, the seal contained Theremin’s sophisticated listening device. The device, later known as “The Thing”, would not be discovered until 1952 — roughly seven years later. The discovery of the great seal listening device is an interesting one. British broadcasters reported hearing American voices on the their radios in the vicinity of the American embassy. No Americans were transmitting though, which meant there had to be a bug. Numerous sweeps were performed, all of which turned up nothing. Joseph Bezjian had a hunch though. He stayed at the embassy pretending to be a house guest. His equipment was shipped in separately, disguised from Russian eyes. Powering up his equipment, Bezjian began a sweep of the building. With his receiver tuned to 1.6 GHz, he heard the bug’s audio, and quickly isolated the source in the great seal. Close inspection of the carving found it had been hollowed out, and a strange device placed behind the eagle’s beak. No batteries or wires were evident, and the device was not powered through the nail which had been hanging the seal. Bezjian removed the device from the great seal and was so cautious the he slept with it under his pillow that night for safe keeping. The next day he sent it back to Washington for analysis.

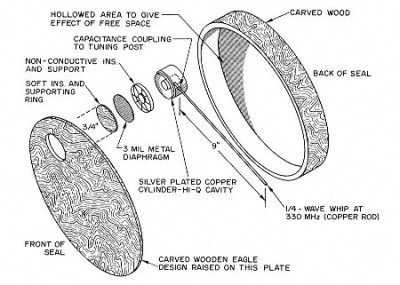

The discovery of the great seal listening device is an interesting one. British broadcasters reported hearing American voices on the their radios in the vicinity of the American embassy. No Americans were transmitting though, which meant there had to be a bug. Numerous sweeps were performed, all of which turned up nothing. Joseph Bezjian had a hunch though. He stayed at the embassy pretending to be a house guest. His equipment was shipped in separately, disguised from Russian eyes. Powering up his equipment, Bezjian began a sweep of the building. With his receiver tuned to 1.6 GHz, he heard the bug’s audio, and quickly isolated the source in the great seal. Close inspection of the carving found it had been hollowed out, and a strange device placed behind the eagle’s beak. No batteries or wires were evident, and the device was not powered through the nail which had been hanging the seal. Bezjian removed the device from the great seal and was so cautious the he slept with it under his pillow that night for safe keeping. The next day he sent it back to Washington for analysis. The great seal bug quickly became known as “The Thing”. It was a passive resonant cavity device, containing no batteries or other power source. It consisted of an antenna and a small cylinder. One side of the cylinder was solid. The other side consisted of a very thin diaphragm, obviously some sort of microphone. Passive resonant cavities had been explored before, both in the US and abroad, but this is the first time we know of that was used for clandestine purposes. In his book Spycatcher, British operative

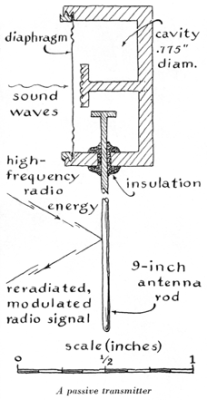

The great seal bug quickly became known as “The Thing”. It was a passive resonant cavity device, containing no batteries or other power source. It consisted of an antenna and a small cylinder. One side of the cylinder was solid. The other side consisted of a very thin diaphragm, obviously some sort of microphone. Passive resonant cavities had been explored before, both in the US and abroad, but this is the first time we know of that was used for clandestine purposes. In his book Spycatcher, British operative  Receive tuning (if it can be called such) was achieved by the precisely cut antenna. The RF carrier transmitted by the Russians would be received at the antenna and travel into the body of the device which was a resonant cavity. That resonant chamber was capacatively coupled to the thin conductive diaphragm which formed the microphone.

Receive tuning (if it can be called such) was achieved by the precisely cut antenna. The RF carrier transmitted by the Russians would be received at the antenna and travel into the body of the device which was a resonant cavity. That resonant chamber was capacatively coupled to the thin conductive diaphragm which formed the microphone. The great seal bug disappeared for a number of years. The Russians knew we had caught them, and moved on to other espionage devices. It finally reappeared in 1960 at the United Nations. During the Gary Powers U2 incident,

The great seal bug disappeared for a number of years. The Russians knew we had caught them, and moved on to other espionage devices. It finally reappeared in 1960 at the United Nations. During the Gary Powers U2 incident, Léon Theremin was released from his camp in 1947. He married Maria Guschina. This time the state did not intervene, and the pair had two children. In 1964, Theremin became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. He lost his job after an article published in the New York times was read by the assistant director of the conservatory. The assistant director stated “Electricity is not good for music; electricity is to be used for electrocution” before throwing Theremin and his instruments out of the establishment. Through the 1970’s, Theremin worked in Moscow University’s Department of Acoustics. While there he built a polyphonic version of his instrument. Stored in a back room, the instrument was looted for parts by students and professors. Meanwhile, Theremin’s instrument was returning to vogue in the western world. Electronic music was hot, spawned by instruments such as the MiniMoog, and the Arp Kitten.

Léon Theremin was released from his camp in 1947. He married Maria Guschina. This time the state did not intervene, and the pair had two children. In 1964, Theremin became a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. He lost his job after an article published in the New York times was read by the assistant director of the conservatory. The assistant director stated “Electricity is not good for music; electricity is to be used for electrocution” before throwing Theremin and his instruments out of the establishment. Through the 1970’s, Theremin worked in Moscow University’s Department of Acoustics. While there he built a polyphonic version of his instrument. Stored in a back room, the instrument was looted for parts by students and professors. Meanwhile, Theremin’s instrument was returning to vogue in the western world. Electronic music was hot, spawned by instruments such as the MiniMoog, and the Arp Kitten.